When Chicago Was the Largest Drum Manufacturer in the World

- Julie Simmons

- Jul 5, 2018

- 12 min read

By Julie Simmons | Music Journalist

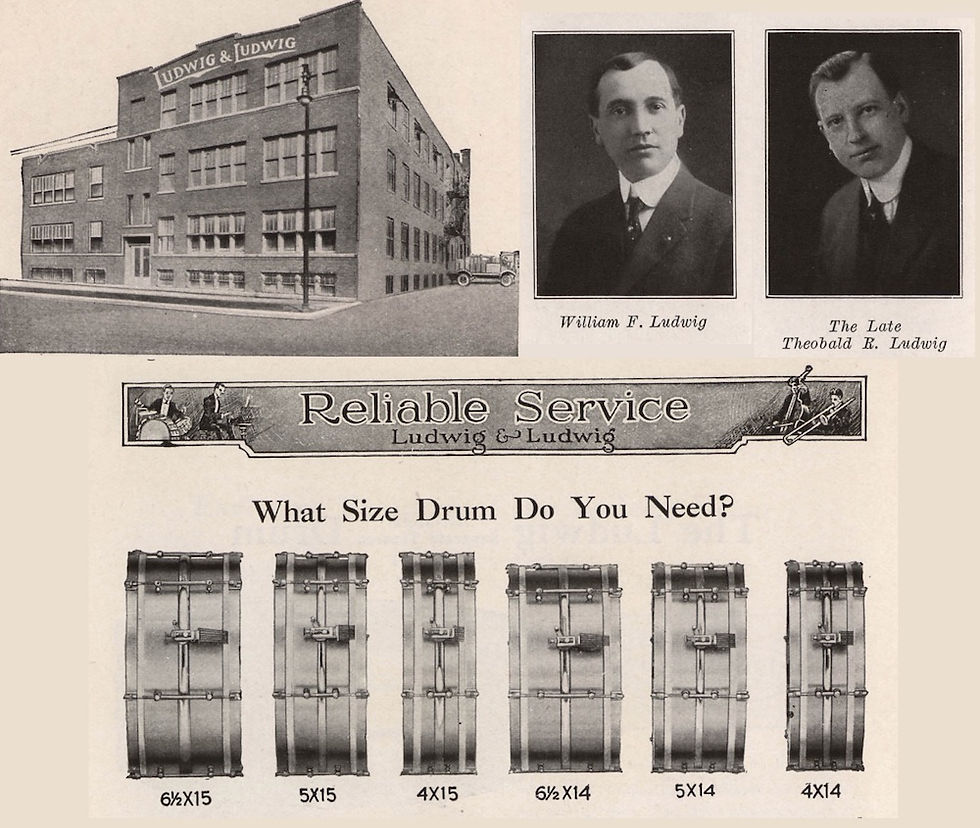

In the early 1920s, a young William Frederick Ludwig (of the Ludwig & Ludwig Drum Company) could be seen sprinting through the streets of Chicago. His mission was to get to the stockyards before the competitor, the Slingerland Drum Company. Flipping through heavy stacks of about 150 raw calf hides, the young entrepreneur would give a cursory examination of each skin and drape the 25 best ones over his arm. After boasting his pick to the competition in the stockyard's reception area, Ludwig would race back to the factory so the carcasses could be made into quality instrument heads. The hides with the fewest blemishes provided the best sound. And during this particular era, the best sounds were coming out of Chicago.

Instrument Production in Chicago

Counterbalancing that humbling stench of slaughtered cattle that Ludwig regarded as “the odor of business” was a bustling area of Chicago once known as Music Row. The buildings lined up on Wabash between Adams and Van Buren must've vibrated from the manufacturing of various musical instruments. Starting around the late 1910s, Chicago was recognized for building player pianos, acoustic pianos, drums, banjos, harps, organs, glockenspiels and other instruments. Its reputation for mass production lasted for decades.

"When I went to college in the early 1970s," begins Rob Cook. "I had a geography professor who said something that really stuck with me. He said about 80% of the world's instruments were made within a 50-mile radius of Chicago. Drums were a part of that era."

Cook is a drum historian. He specializes in writing and publishing histories for drum companies as well as biographies of drummers. His company, Rebeats, is also responsible for organizing and promoting the country's oldest and largest vintage and custom drum expo known as the annual Chicago Drum Show. Through his years of extensive research and writing, Cook identified the biggest players in the drum world that spanned across Chicagoland between 1900-1980. Among the music giants were: Franks Drum Shop (intentionally spelled without the apostrophe), Slingerland Drum Company, The Leedy Drum Company, Ludwig & Ludwig Drum Company and the Camco Drum Company.

Cook starts with a simple observation, “Chicago’s always been a manufacturing town with access to transportation.”

It’s true.

The Midwest’s natural resources made the production of drums extremely convenient. Although the mahogany used for some drum shells was likely imported from Central America, the more common shells would’ve come from maple trees which are indigenous to the Midwest. Also at that time, Chicago's healthy infrastructure -- including Gary, Indiana’s steel mills -- offered plenty of metal for producing rims, lugs, brackets, thumb screw rods as well as the heavy machinery necessary for drill presses and lathes. And of course, the infamous Chicago stockyards conveniently provided the skins for "calf heads” before they were replaced by plastic.

In addition to natural resources, Chicago’s location along Lake Michigan and major railroad lines were ideal for transporting goods. Musicians didn’t need to live in the city to get Chicago-made instruments. They could order their selection from a catalog and have it delivered to the doorstep. The Dixie Music House (located on what’s now Wells St.) published and composed music, delivered instruments and specialized in the selling and repairing of percussion instruments for jobbing drummers.

So, yes, Chicago was a prime location for music manufacturing. However, as Cook adds, “So were Boston, Philadelphia and even New York." These well-established cities also had natural resources, a strong infrastructure and efficient transportation of goods. In fact for over a century, the East Coast was the leading manufacturer of drums partly because it was able to provide percussive accommodations during several American wars.

In an article titled, "Boston’s Historic Drum Makers," Lee Vinson explains how “Boston, and the greater New England, had been a center for drum building going back to the days of the Revolutionary War" and how this tradition of supplying war drums continued through the Civil War. Cook attests that Boston was the largest drum manufacturer before the business shifted over to Chicago.

How, then, did the East lose its foothold in being the leader in music manufacturing? The answer seems to be a revolution within the entertainment industry.

Chicago’s Hollywood Era

In the early 1900s and before Hollywood, Chicago was the capital of the motion picture industry; heralding more movie studios and filmmakers than any other U.S. city. According to the Encyclopedia of Chicago, by 1907, there were more movie theaters per capita in Chicago than any other city in the United States. Actors, directors, set designers, make up designers, wardrobe designers, carpenters and electricians flocked to the city while word spread that there was also a demand for musicians. Movie directors relied on musicians to perform while filming to motivate actors. They were also needed to play during public screenings in lieu of spoken dialogue.

While organists might’ve been the most recognizable player in theaters, percussionists were responsible for drums as well as special effects. For effects, percussionists used devices to imitate horse hooves, Indian drums (band-sized and orchestra-sized), gun shots, boat whistles and train whistles. And, once again, companies like Dixie Music House and Ludwig & Ludwig were there to support this new entertainment scene by providing these sound effects.

Before long, Chicago musicians became almost as famous as movie stars making this urban area not only a travel destination but a place to settle down. From 1900 - 1910, Chicago’s population would increase by almost 30% and it wasn’t about to stop growing.

Starting in 1916, the country would undergo a major population shift; a notable one taking place between New Orleans and Chicago.

The First Great Migration

During America’s first Great Migration (which started around 1916), over a million African-Americans fled poverty and Jim Crow laws in the South in search of a better life. Those who lived in New Orleans traveled directly north by way of the Mississippi River into Illinois. Within a matter of years, hundreds of thousands of Southerners would travel east from the Mississippi and settle in Chicago. As these multi-generational families moved to Chicago, they brought remnants of their culture with them, including Dixieland Jazz (aka “Hot Jazz”). Joseph Nathan Oliver (aka “King Oliver”), was one of the first renowned jazz band leaders and clarinet players to transplant himself from New Orleans to Chicago.

This is an important historical point: If the musicians coming from the South had been solo artists carrying ukuleles, it might not have had a huge impact on Chicago’s music scene or industry. But whenever jazz parked itself in a city, the demographics and businesses were affected. Jazz bands brought along an ensemble of musicians playing various instruments. They brought along future generations of players and musician friends. As an example, King Oliver delivered one of the best jazz drummers of all time, Warren “Baby” Dodds and eventually, Louis Armstrong too.

By now, the instruments that continued to be manufactured on Music Row were directly serving the growing, local movie and music industries. Meanwhile, on the city's South Side (along State between 31st and 39th) a vibrant entertainment district known as "The Stroll" was emerging. While jazz was still very popular in cities like New Orleans and New York, by the 1920s, Chicago was officially the jazz capital of the world. What’s more, Chicagoans were playing their own style of jazz differently in comparison to these other regions.

Whereas New Orleans’ Dixieland Jazz played with a bass drum player and a snare player to a marching beat, Chicago’s style used a drum set and a two-beat with accents on the one and three. And while jazz bands in the South were always committed to playing songs together; in Chicago, audiences anticipated ensemble performances breaking off into drum solos and other solo performances. Suddenly, playing in a jazz band wasn’t just about being part of the group, it was about celebrating the individual. And when musicians started being regarded like movie stars, it was as if the film world had merged with the music world.

In addition to the live jazz scene and motion picture industry, Chicago was also dominating the airwaves with the WLS National Barn Dance radio program, in the mid-20’s. The radio show became so popular that the station built a studio at the Sherman Hotel downtown so they could record shows in front of a live audience. And because of WLS’s 50,000 watt signal, the Barn Dance would reach a broad audience across the U.S., turning radio personalities into minor celebrities.

Much like the way drummers were needed for early motion picture films, they also provided instrumentation for radio programs. The percussionist for the Barn Dance program, Roy Knapp, would leverage his experience and reputation to open the Roy C. Knapp School of Percussion in Chicago. And over the next several decades, Knapp transformed drumming students into drumming icons. Some of his pupils included: Louis Bellson, Hal Blaine, Bobby Christian and Gene Krupa.

But, for now, World War I as coming to an end which meant that people would soon be looking to music to provide context for the times. Businesses like Ludwig & Ludwig as well as H. H. Slingerland waited with anticipation over what would happen next.

WWI, Drums and Banjos

In an article entitled, "A Thumbnail History of the Banjo," banjo historian, Bill Reese, describes how WWI actually ignited our country’s interest in the unique stringed instrument. He writes, "After the First World War [1918], America entered a time of isolation and turned to 'American made' music for pleasure. Jazz entered the picture and the banjo became an integral part of the early jazz bands."

As discussed, Chicago drum manufacturers had been supplying the local jazz scene since the first Great Migration. But now the country was asking for more jazz and more banjos. Fortunately, it was easy for drum companies to meet the demand for banjos. Calf skins were perfect for tanning, stretching and tucking over drumheads and banjo heads. What's more, the same machine presses used to bend maple into their round shells for drums could also be used to shape banjo-heads and small hand drums.

H. H. Slingerland was already in the business of making its own banjos and ukuleles. They didn't see the need to make drums and instead remained steadfast on making their stringed instruments. That is, until Ludwig & Ludwig decided to chase the trend and add banjos to their inventory.

In The Ludwig Book, Cook writes, "The concept of spending a lot of money to gear up for banjo production probably sounds a little absurd to today's reader. It is important, however, to remember the musical context of the day. The banjo was a dominant string instrument from the 1920s all the way back to the 1700s. It was inconceivable in the 1920s that the banjo would decline in popularity. Does anyone today suspect that the guitar will decline in popularity?"

Even though these companies were investing in banjos, for three companies, it was all about selling the drums. Throughout the 1920s, there was constant ping-ponging between Leedy’s (Elkhart, Indiana), Slingerland and Ludwig as to which was the world's largest drum company. Meanwhile, the sharp decline in the banjo’s popularity would fail to provide an adequate return on investment, especially for Leedy’s and Ludwig & Ludwig.

The Great Depression

The end of WWI is said to have encouraged Americans to call for the brightness of jazz. Yet when tragedy struck the mainland with the Great Depression that started with the Stock Market Crash of 1929, there would be an almost immediate recall on the sound of the banjo.

To quote banjo player, Robert Webb, "Demand for its bright, happy sound disappeared almost overnight. Professional orchestras made a quick transition to the ‘arch-top’ guitar, developed in the 1920s by Gibson and others which provided a mellow and integral rhythm more in keeping with the subdued nature of the times." Both Slingerland and Ludwig & Ludwig were hit hard by the plummet in banjo sales.

Almost concurrently, Chicago’s film industry fell apart. First, filmmakers fled Chicago, migrating southwest towards a more stable climate in California. Also, Cook reports in The Ludwig Book that when the Vitaphone was invented and transformed silent films into talkies, “over 18,000 professional drummers lost their jobs in less than two years.”

As a result of the massive hits to both industries, Ludwig & Ludwig sold the family business to C. G. Conn (which also owned the Leedy Drum Company) in Elkhart, Indiana. Ludwig’s departure from Chicago’s epicenter marked the first unraveling of an era. In 1937, a few years after selling the business, William F. Ludwig II returned to Chicago and started the WFL Drum Company (leveraging his initials since he no longer owned the rights to his own surname).

Although Chicago had been hit by the Great Depression and the abrupt loss of the local movie industry, a major comeback was on the horizon, especially for the Ludwigs.

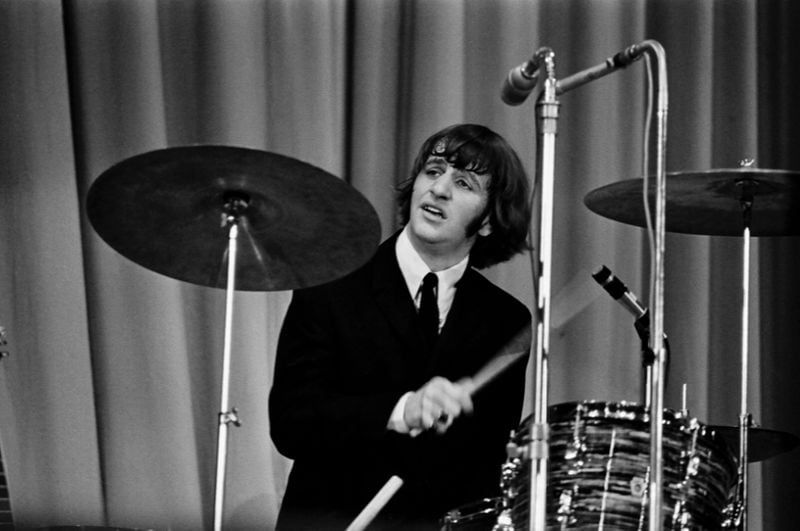

The Ringo Effect

For decades following WWII, the competition between the WFL Drum Company, Ludwig, Leedy, Camco and Slingerland was fierce as manufacturers sought out famous drummers to represent their brand. It’s been noted that one of the reasons Chicago’s Camco Drum Company failed to succeed during this highly competitive era was because they hadn’t aligned themselves with a celebrity drummer. For years, Slingerland had touted star drummers who played their kits like Gene Krupa, Buddy Rich, Jimmy Vincent and Tito Puente. Fortunately for the Ludwig family, they were able to buy back their name in 1955, just in time for The Beatles’ drummer, Ringo Starr, to make Ludwig the world’s most popular brand in drums yet again.

In The Making of a Drum Company: The Autobiography of William F. Ludwig II, Ludwig Jr. describes how his business had to fulfill orders immediately following The Beatles’ appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show in February of 1964.

Ludwig Jr. dictates, “We had to crank up a night shift that started at 5:00 P.M. and ran until 1:00 A.M. six days a week. We were turning out 100 sets per day with a crew of about 500 employees on two shifts. And, at the same time, we were buying up and digging up the neighborhood for expansion. Remember that we were expanding into a residential neighborhood. We started to receive complaints about the noise at night. The wood shop machines in particular were keeping them awake all hours of the night. I had to visit the neighbors up and down the block on Wabansia Avenue as well as Damen Avenue and invite them to the plant tours followed by ‘jollification’ at Boris’s bar afterwards. We finally had to shut down certain machines like the stick lathes and scarfing machines at 10:00 P.M. to quiet the neighborhood.”

Ludwig Jr. adds, “Half of the two hundred or so on the night shifts were zombies! There were frequent fist fights in the alley behind the plant. It was a constant challenge, but we kept pretty close to our quota – 100 sets per day, mostly in oyster black pearl and all with the Ludwig logo on the front head of the bass drum.”

The Post Beatles Era

Even after the demand for Ringo drums settled down, William (Bill) F Ludwig III confirms that the competition between Ludwig and Slingerland remained strong. Just as in the days when William F. Ludwig would race to the stockyards to try and beat the Slingerlands from getting the best hides, Bill says his dad maintained this competitive spirit even into old age. Bill recounts one Saturday morning, when his dad woke him up:

“He said, ‘C’mon, we’re taking a ride.’ And I started to follow him out to the garage. ‘Where are we going?’ I asked. ‘We’re going to the Slingerland Drum Company and I’m going to go through the dumpster to see what they’re working on and you’re going to watch for the police. And I said, ‘No! I’m not having anything to do with that!’ So, he went by himself and he came home with a bunch of shells from the dumpster. He took it all back to our engineers and said, ‘They’re working on the three-ply. Why aren’t we working on that?’ Or, ‘They’re working on a new strainer. Why aren’t we working on a new strainer?’ My dad would also drive by the Slingerland parking lot to count the cars and see how many employees they had.”

At the 2017 Chicago Drum Show, Bill points to a black and white photo of his highly ambitious father testing drums at the WFL Drum Company factory. The image reminds Bill of the moment he decided to start up WFLIII Drums when, years earlier, he’d sold the family name to the Selmer Company (now Conn-Selmer, Inc.).

Bill reminisces as he gazes at the photo, “I had been out of the music business a long time. I missed it terribly. It’s where my heart and love is. Three years ago, I took that picture off my kitchen wall just--”

Bill pauses a moment in an attempt to articulate the mysterious urge. Then, he continues, “I took that picture for some reason. On the back, in my father’s handwriting, he had written: Senior starting over age 63. He lived to be 93 and was in the factory, every day, until he died. So, I had just turned 60 and I thought, Goddamn it! If he can do it, I could do it!”

So What Does it All Mean?

If one imagines a time when Chicago was a hotbed for music in the early 1900s, the sound waves emitted across the globe might’ve acted like a clarion call for more musicians and more sound; as if Chicago was trying to produce a heartbeat for the entire planet. If history repeats itself, Chicago will once again become a migratory destination and a hotbed for new music.

***

This article was originally published in DRUM! magazine in Summer 2018.

Do you like to talk about music in a way that's intellectual, civil and collaborative? Ask to join the Facebook Group, Music Makes You Think.

Comments